20 Reason Why Gathering Life History Is Important With Dementia

20 Reasons Why We Want to Know the Early Life History of Older People With Dementia?

“After everything I am doing, marching like escort, the child I was years ago, the boy in his first love that I was, the soldier that I was in those days, and the gray hair that I was one hour ago” – Yehuda Amichai

1. The right of older adults with dementia is to be with people who know their life story including cultural habits and religious faith (Bell & Troxel, 2003).

2. Developing friendships, relationships, and trust with people with dementia is the foundation of person-directed care (Bell & Troxel, 2003; Zgola, 1999). Knowing, understanding, and using the life history of the person with dementia is the key to creating and maintaining this foundation.

3. The only way to truly understand an individual in later life in a holistic manner is to see her or him in a life-course perspective.

4. Although more and more cueing is required as the disease progresses, the long-term memory remains relatively intact until the later stages of Alzheimer’s Disease. Therefore, there is a need to “capitalize on what can be remembered from the distant past to help counter the threat to personhood” (Chaudhury, 2002).

5. “Neurodevelopmental Sequencing Approach” in Dementia: Behavior, movement, and functional losses in people with dementia occur in approximately the reverse order of their original development (Buettner, & Kolanowski, 2003). Functional abilities, skills, and activities a person acquired, learned, and enjoyed in infancy, childhood, and early adult life may be relatively preserved into the later stages of dementia. This key principle can be described as “What Goes In First, Goes Out Last.”

6. To be able to have a meaningful interaction and communication with the older person with dementia (e.g., conversation prompter) and to be able to attribute meaning to seemingly incoherent speech (Chaudhury, 2002).

7. To be able to identify, focus, and capitalize on the person’s remaining abilities (yes, we need to understand and proactively compensate for the lost abilities but we also need to avoid focusing excessively on these lost abilities). Due to the progressive nature of Alzheimer’s disease, this is a “moving target” that requires regular assessment and adjusment.

8. To be able to plan, encourage, and engage the person in enriching, appropriate, and meaningful activities based on her or his life-long interests, current abilities, disabilities, and preferences. This, while remaining open to the possibility that life-long interests may change in certain individuals.

9. To understand the meaning of behavioral expressions for the person (Rasin & Kautz, 2007). For example, to be able to identify and address remote triggers from the distant past of distressing behaviors (Landerville et al. 2005). Research and practice have demonstrated a relationship between various early-life stressful events (e.g., life-threatening experiences and traumas) and current distressing behaviors (Cohen-Mansfield & Marx, 1989; Feil, 2002).

10. To be able to design a physical environment in a way that is personalized, familiar to the individual, understandable, and consistent with her or his lifelong positive experiences such as in their homes. This, from general design of physical spaces to cultural, ethnic, and familiar symbols, favorite and personally meaningful objects, and furniture. This, while continuously adapting the physical environment to the person’s cognitive disabilities.

11. To know what in the person’s life gives her or him hope (Kivnick, 1993) and to use this knowledge to nurture this sense in the present.

12. To know what it is in the person’s life (from her/his perspective) that is most worth living for or that makes her/him feel most alive (Kivnick, 1993).

13. To know whom or what the person especially cares about (Kivnick, 1993) and use this knowledge to plan conversations, activities, and care.

14. To know the things that have always given the person confidence and made her or him proud (Kivnick & Murray, 2001) and use this knowledge on a regular basis to promote those feelings and experiences in the person.

15. To know the person’s fears and to make every effort to avoid situations, conversations, activities, and care tasks that trigger those fears.

16. To be able to anticipate and proactively address the person’s physical, emotional, psychological, social, occupational, cultural, and spiritual needs. Various unmet needs related to the person’s psychosocial history often contribute to distressing behaviors (Whall & Kolanowski, 2004).

17. Many family members want to remain involved in the care of their relative when the person lives in a long-term care residence (such as a nursing home or an assisted living residence). Learning about the unique life-history of the person is a great way to involve family members in her or his care (Chaudhury, 2002). This, in turn, could inform and lead to more individualized and effective care.

18. To be able to develop an individualized care plan that respects the person’s values, beliefs, faith, personality, lifestyle, daily routine, habits, coping style, areas of sensitivity, fears, traumas, accomplishments, expectations, interests, special skills, likes, dislikes, hobbies, and preferences.

19. To relate to the person with empathetic identification and make her/him feel that she/he is understood as a real person (Chaudhury, 2002).

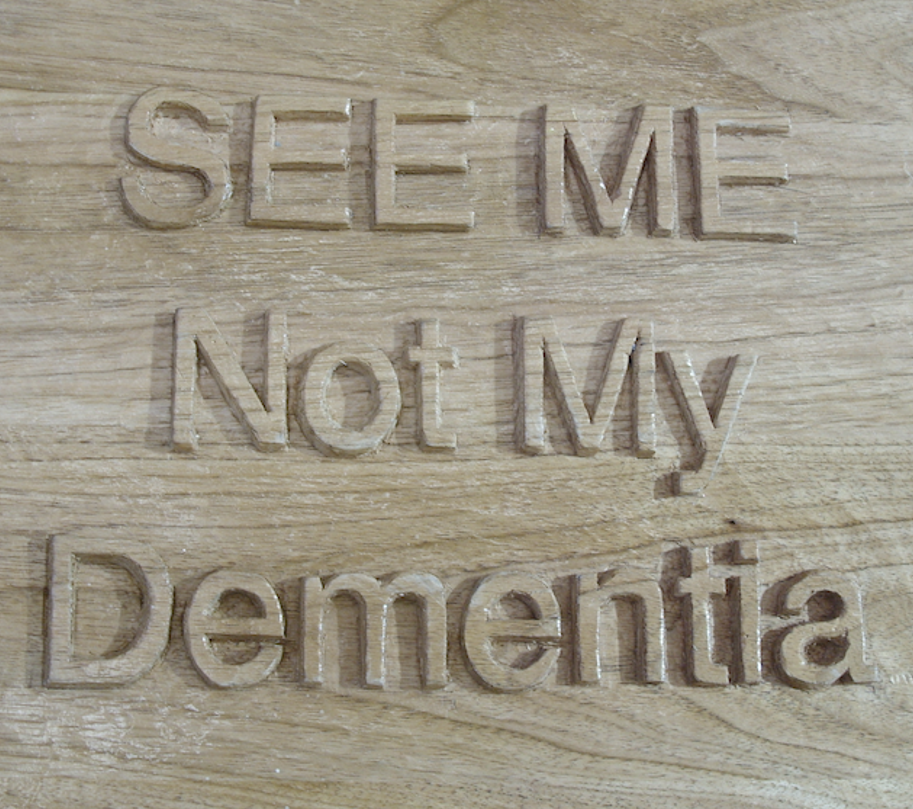

20. To be able to see the person behind the dementia and/or her/his behavioral expressions and to preserve her or his personhood, identity, sense of self, and dignity as long as possible (Kitwood, 1997).

Wood carved piece made out of Butternut. Wood Carver: Eilon Caspi

Wood carved piece made out of Butternut. Wood Carver: Eilon Caspi

References

Bell, V., & Troxel, D. (2003). The best friends approach to Alzheimer’s care. Baltimore: Health Professions Press.

Buettner, L. & Kolanowski, A. (2003). Practice guidelines for Recreation Therapy in the care of people with dementia. Geriatric Nursing, 24(1), 18-25.

Chaudhury, H. (2002). Place-biosketch as a tool in caring for residents with dementia. Alzheimer’s Care Quarterly, 3(1), 42-45.

Cohen-Mansfield, J & Marx, M.S. (1989). Do past experiences predict agitation in nursing home residents? International Journal of Aging and Human Development, 28(4), 285-294. Feil, N. (2002). The validation breakthrough: Simple techniques for communicating with people with Alzheimer’s-type dementia. (2nd edition). Baltimore: Health Professions Press.

Kitwood, T. (1997). Dementia Reconsidered: The Person Comes First. Berkshire, UK: Open University.

Kivnick, H.Q., & Murray, S.V. (2001). Life strengths interview guide: Assessing elder clients strengths. Journal of Gerontological Social Work, 34(4), 7-32.

Kivnick, H.Q. (1993). Everyday mental health: a guide to assessing life strengths. Generations, 17(1), 13-20.

Landerville, P., Dicaire, L., Verreault, R., & Levesque, L. (2005). A training program for managing agitation of residents in long-term care facilities: Description and preliminary findings. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 31(3), 34-4.

Rasin, J., & Kautz, D.D. (2007). Knowing the resident with dementia: Perspectives of assisted living facility caregivers. Journal of Gerontological Nursing, 33(9), 30-36.

Whall, A.L. & Kolanowski, A.M. (2004). The need-driven dementia-compromised behavior model – a framework for understanding the behavioral symptoms of dementia. Aging & Mental Health, 8(2), 106-108.

Zgola, J.M. (1999). Care that works: A relationship approach to persons with dementia. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press.

Additional Resources

Dementia Chats Last Session is Below

Listen to the Archived Shows!

Sign Up Now and Be Prepared if Wandering Would Occur

Search For Information Or

Add Your You Services For Other To Find!